Selene Rivas - November 24, 2017

(CW: suicide)

“A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done. If a story seems moral, do not believe it. If at the end of a war story you feel uplifted, or if you feel that some small bit of rectitude has been salvaged from the larger waste, then you have been made the victim of a very old and terrible lie. There is no rectitude whatsoever. There is no virtue. As a first rule of thumb, therefore, you can tell a true war story by its absolute and uncompromising allegiance to obscenity and evil… You can tell a true war story if it embarrassses you. If you don’t care for obscenity, you don’t care for the truth; if you don’t care for the truth, watch how you vote. Send guys to war, they come home talking dirty.” - Tim O’Brien (The Thing They Carried)

“A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done. If a story seems moral, do not believe it. If at the end of a war story you feel uplifted, or if you feel that some small bit of rectitude has been salvaged from the larger waste, then you have been made the victim of a very old and terrible lie. There is no rectitude whatsoever. There is no virtue. As a first rule of thumb, therefore, you can tell a true war story by its absolute and uncompromising allegiance to obscenity and evil… You can tell a true war story if it embarrassses you. If you don’t care for obscenity, you don’t care for the truth; if you don’t care for the truth, watch how you vote. Send guys to war, they come home talking dirty.” - Tim O’Brien (The Thing They Carried)

In a 2005 issue of the academic journal "Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies", two men had a public spat, recorded in three published pieces. One man was Lawrence Suid, a film historian who's written several important works on the historical relationship of the Pentagon and Hollywood, one of the most famous titled Guts and Glory. The other, David L. Robb, freelance journalist, and three-time Pulitzer prize nominee. The argument started from Lawrence Suid's review of David L. Robb’s book: Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies. He dismissed the claims found in the book that the Pentagon exercises a form of censorship in films by leveraging their vast amount of resources (both monetary and in equipment) to change and modify movie scripts. For Suid, it isn't censorship but rather common sense: "...the military has no obligation to support any film. The refusal to do so simply does not constitute censorship."1. (Claims similar to Robb’s can be found in the following by Tom Secker and Matthew Alford.)

Whether what the Pentagon is doing is nefarious enough to be called censorship or not, it is true that they wield enormous amount of influence through their resources. Although Suid is correct in saying that a filmmaker can still produce something without these resources, it'd be hard to match a film aided by the military in terms of reach and production value. It's not that the military should give the same access to the resources to everyone, but instead that their participation skewes the narrative too much in their favor. As producer Duncan Berg, of the film Battleship, said:

“You couldn’t make Battleship without the help of the military. It would have cost tens of millions if you could even make it work at all...To take any one of these ships out to sea the fuel costs alone would be astronomical. But they’re going out already — you pay for costs that are over and above what they’re doing.”2

So in what ways exactly can the Pentagon help Hollywood moviemakers?

- Lend expensive army equipment, such as jets, ships, tanks, and other items in their arsenal for free, or at incredibly cheap rates. For instance, in the first film of the latest Superman movie series, Man of Steel, the U.S Army lent the production team “one Chinook helicopter, two Black Hawk helicopters, two Abrams tanks, two Bradley Fighting Vehicles, two Stryker Vehicles, and six Humvees” for free.3 Other branches of the armed forces, such as the Air Force, also helped by lending them “a C-130 transporter for $25,239.70, including personnel” and “helicopters and operators for $253,628.41”.4 All in all, these expenses totalled less than 1$ million dollar of the 200$ million dollar budget.5

- Waving location fees, or offering them at cheap rates. This was the case of Peter Berg’s Lone Survivor, filmed at an Airforce base in New Mexico, as well as Man of Steel, shot in Edwards Air Force Base.6

- Providing cheap or even free personnel for films. Soo Youn from Fortune Magazine writes: “With the use of active duty military personnel who are currently training, filmmakers are also able to skirt the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) daily minimum rates ($153 for eight hours plus overtime) for unionized actors. Then they save again by not having to pay residuals.”7

In return, what’s the price they pay? To quote Duncan Henderson again: “It’s a world of finite resources: manpower, time-wise, jet-wise, they’re going to give it to whoever they think can help their cause and basically put the military in a good light.”8 Some scripts require revisions and changes done by people in the Pentagon. As one of them, Captain Russell Coons, explains regarding the film Captain Phillip (that required no script change), it was “an opportunity to highlight our capabilities and showcase Navy’s anti-piracy and maritime security operations to a worldwide audience.”8

Taking into consideration the previous article in which we discussed how media and popular culture can be used to normalize certain ideas and behaviors, and now we understand how the power to do so is wielded consciously. Understanding the effects and ways in which this influence manifests is an incredibly extensive subject of study; there are many different ways in which this problem could be approached, different questions that can start us in our approximations. For instance, what is or isn’t a war film? Can a film not about the war be militarized? What behaviors or thoughts do these films propagate?

An example of an approach that could be taken is, for instance, the following one, suggested by Jason Dittimer, (who was quoted on a previous installment of this series):

“...popular culture does not determine who we think we are, who we think the enemy is, or how we will react in a crisis. Rather, popular culture provides many different sets of resources that may be activated under appropriate circumstances. It is a set of capabilities, or lines of flight, that are powerfully world-shaping, but not powerful in the traditional sense ”9

In this point of view, popular culture can define, rather than concrete thoughts and actions, what is possible or not, this way shaping the world. So for instance, it can define violence as a solution for certain situations or a necessary evil that certain individuals or societies have to undertake.

Having understood the strong influence the military exerts on many widely-consumed Hollywood films, the question is then: can what is essentially propaganda for those whose sole purpose is war and war-making depict the unflattering, contradictory, and gruesome realities, not just of war, but of the institution that sustains it (i.e, the military)? In other words, can we expect a film supported by the armed forces to make any sort of anti-war statement? Ultimately, how can a film inform us about war, and what does an anti-war stance look like on film? This article will instead try to understand war films as one of the primary ways in which a general audience learns about the experience of war, how this informs their reality, and what are ways in which pro and anti-war stances can be explored in film.

While we might get a lot of images and stories about war in television news or newspapers, in film we find an immersive, sensory facsimile of reality. It is no longer about the factual, who attacked whom or where, with what weapons or what purpose; instead, we get a sense of what war could seemingly look, sound, or feel like. The media pretends to be objective; the camera doesn’t pretend to represent an individual point of view, but is instead dispassionately attempting to capture “reality”. Film, however, is a subjective experience. The camera shakes, moves, falls. It can represent the confusing experience of the battlefield, and this, paired with other narrative and visual devices, can create an immersive experience. The effectiveness of these devices has made it so the lines between films and reality are increasingly blurred:

“The frequently heard refrain from the 11 September 2001 attacks, that ‘it was like watching a movie,’ illustrates how the human body, and its cognitive sense-making abilities, are shaped by ongoing engagements with particular ways of seeing/knowing embedded in popular cultural forms and with the generic forms of narration that accompany those forms…”10

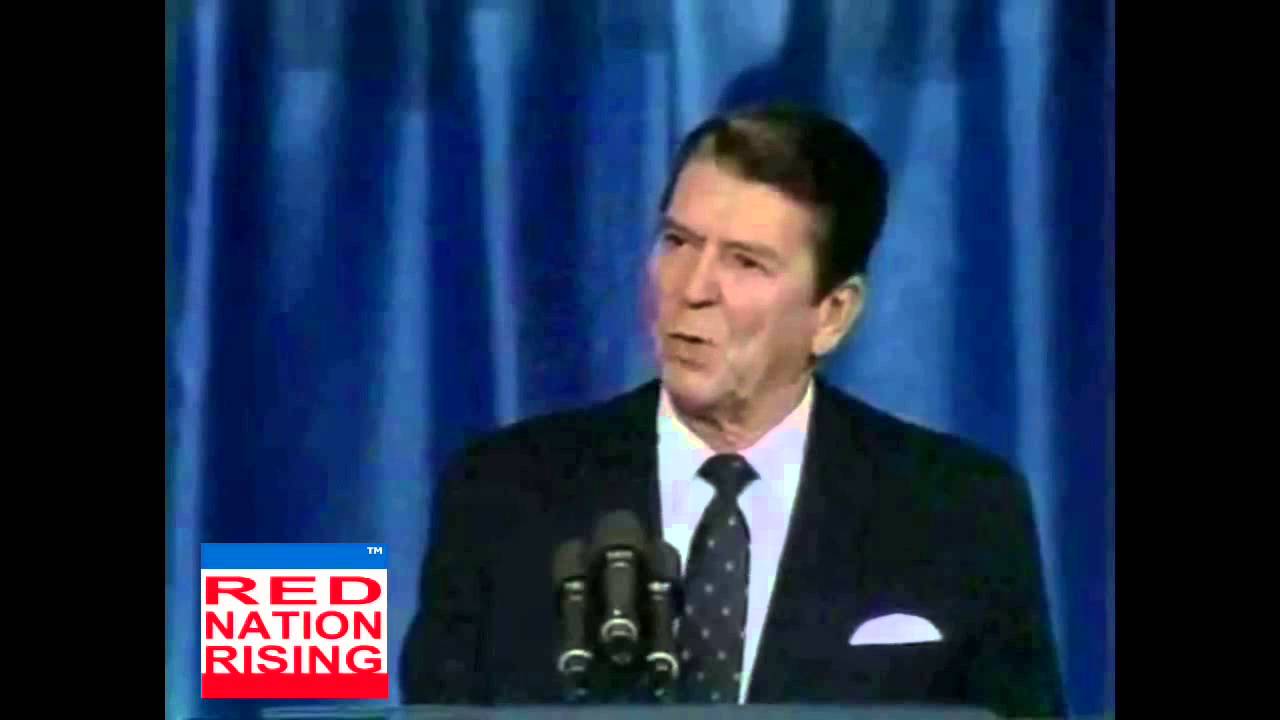

Thanks to a vast historical catalogue of films (in this case war and disaster films), and the general ways these films tend to depict certain events, sometimes we understand reality through that lense, and in turn hold certain expectations about what certain things should or shouldn’t look like, or what response would be appropriate. In other words, movies doesn’t merely inform us of a factual reality, but instead it presents to us a way of interpreting the world and what to expect from it. This is consciously used by media and other important political figures, “... such as ex-Hollywood actor Ronald Reagan, [who] appeared to understand that Cold War geopolitics could be assembled and reproduced in filmic terms.” 11 For instance:

When President Reagan described the Soviet Union as the ‘evil empire’ in 1983, commentators were swift to detect thinly disguised parallels with the Star Wars franchise....Reagan’s dress, speech and demeanor were attuned and attentive to popular cultural references. He dressed and acted the part of statesman, cowboy, commander in chief and folksy everyday man. He quoted lines from Clint Eastwood movies and other films, including Rambo: First Blood (1982). 12

When President Reagan described the Soviet Union as the ‘evil empire’ in 1983, commentators were swift to detect thinly disguised parallels with the Star Wars franchise....Reagan’s dress, speech and demeanor were attuned and attentive to popular cultural references. He dressed and acted the part of statesman, cowboy, commander in chief and folksy everyday man. He quoted lines from Clint Eastwood movies and other films, including Rambo: First Blood (1982). 12

This in turn can be a powerful tool for defining war for an entire generation. General MacArthur, for instance, praised John Wayne’s interpretation of Sergeant Stryker in Sands of Iwo Jima “...before the American Legion Convention by affirming ‘You represent the American serviceman better than the American serviceman himself.’”13 And indeed, when attempting to make another war movie, this time about the Vietnam War, called Green Berets, “...Wayne promised President Johnson that The Green Berets would ‘tell the story of our fighting men in Vietnam with reason, emotion, characterization and action. We want to do it in a manner that will inspire a patriotic attitude on the part of our fellow Americans.’”14 However, something went awry in how the American public perceived the film, which was critically panned.15

Indeed, something had changed within the public; no longer was the unabashed militarism present in pre-Vietnam, World War II cinema, celebrated. Works of fiction written by Vietnam war veterans, as well as the general toll the war had taken on the American population made gung-ho, patriotic propaganda such as Sands of Iwo Jima and Green Berets, less palatable. Where Hollywood could easily turn the Axis and Allies, the atrocities committed by the first and the heroism displayed by the second, into sensational stories with clear enemies and moral lessons, the Vietnam war posed a challenge. World War II films make grand statements about moralities, values, and the justification of all the individual and collective turmoil that war might imply, while “...Vietnam films and fiction attack military and political authority: there is no legitimate higher authority, and nobody can determine absolute right and wrong, make moral judgments, or find meaning in the war.”16

Let’s take compare two similar characters, one from Sands of Iwo Jima, and another from Full Metal Jacket. In essence, both films are showing us the same thing: tough commanding officers who profess to whip the group of marines into shape.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SXyouaMGOzo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wlcuPNv8Od8

Although they both end in tragedy for these characters, each film portrays the final result of their “tough love”; for the men in Sands of Iwo Jima, Stryker’s death is regrettable, but part of a larger mission. “Alright, saddle up, let’s get back in the war!” one exclaims, after the flag has been planted, an objective has been won. His influence is ultimately positive, making boys into men, and the film ends on a high note, with a hymn being sung as the heroes dissolve into the mist, presumably to continue their teacher’s legacy.

In Full Metal Jacket, Sergent Hartman dies at the hands of his own creation, the tormented Private Pyle, who then goes on to kill himself. It is not painted heroically, necessary, borne out of duty. It is, however, a direct result of Hartman’s teachings, and he dies proud of the killer he created. Ultimately, "rather than being moulded into an efficient and noble group of all-American boys by a harsh but decent sergeant, the recruits have their humanity stripped away in horrifying fashion. "17

In Full Metal Jacket, Sergent Hartman dies at the hands of his own creation, the tormented Private Pyle, who then goes on to kill himself. It is not painted heroically, necessary, borne out of duty. It is, however, a direct result of Hartman’s teachings, and he dies proud of the killer he created. Ultimately, "rather than being moulded into an efficient and noble group of all-American boys by a harsh but decent sergeant, the recruits have their humanity stripped away in horrifying fashion. "17

This movie, based on a book called Short Timers by Gustav Hasford (who also helped with the screenplay), is directly informed by World World II era myths, such as Sands of Iwo Jima. The first line spoken by the protagonist, Private Joker, directly references John Wayne (“Is that you John wayne? Is this me?”), and in the book, soldiers laugh at a screening of The Green Berets, saying “This is the funniest film we have seen in a long time.”18

Where did this disconnect come from? This intense image of grief and horror at the war, not being redeemed, justified, glorified, or sensationalized beyond the sheer spectacle of carnage? And, most importantly, can we find any such example today of war not being depicted as noble nor even necessary, but instead a terrible enterprise where people are ordered to kill other people? Any questioning of authority, military force and the necessity to use it?

It was during the Reagan era that war movies returned to their propagandistic purposes. As the article quoted several times above states when talking about the Rambo franchise, Hollywood repurposed the Vietnam war so that “...American soldiers did not lose but were betrayed.”19 A new war was being waged, if not in any battlefield, through popular culture. Soviets and communists were the new enemy. It might be a stretch to consider Rocky IV being a war film, but Silvester Stalone, just like in Rambo, represented America, ready to make a stand against the “Russian menace”.

While an argument could be made that film mainly serves as an escape from an already grim reality, they also inform large groups of people about what war looks, feel, sounds like, and means. By neglecting to represent certain, well-documented realities about veteran PTSD, suicide rates, sexual violence, they are deceitful. Whenever we are presented with the image of a soldier or the military in film, we should ask ourselves, who is benefiting from this depiction? What is being left out?

For some highly recommended video essays on war films, militarism, and propaganda, please look at these links:

References:

1 Suid, Lawrence H. “Lawrence Suid's Response of 7 January 2005.” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies, Center for the Study of Film and History, 23 May 2005, muse.jhu.edu/article/183029.

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Youn, Soo. “Hollywood's Military Complex.” Fortune, Fortune, 19 Dec. 2013, fortune.com/2013/12/19/hollywoods-military-complex/

9 Dittimer, Jason. “On Captain America and 'Doing' Popular Culture in the Social Sciences.” E-International Relations, www.e-ir.info/2015/05/05/on-captain-america-and-doing-popular-culture-in-the-social-sciences/

10, 11, 12 Dodds, Klaus. “Hollywood and the ‘War on Terror’: Genre-Geopolitics and ‘Jacksonianism’ in The Kingdom.” Popular Culture and World Politics, E-International Relations Publishing, 2015, journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1068/d7609.

13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Newman, Simon. “‘Is That You John Wayne? Is This Me?’ Myth and Meaning in American Representations of the Vietnam War.” American Studies Today Article, Liverpool John Moores University, www.americansc.org.uk/Online/Newman.htm.

Series Homepage at http://nnomy.org/index.php/en/resources/blog/researching-militarism-selene-rivas

Selene Rivas is an anthropology student at the Central University of Venezuela and an intern for the National Network Opposing the Militarization of Youth. Contact her at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

###

Over the course of this series, we have explored several concepts which are building blocks for the social sciences (“normal”, “normalization”), which in turn have helped us understand and define “militarism” and “militarization”. After this, we dove into the transformative potential found within popular culture: how can it affect the people who consume it? Linking this very powerful influence to previously defined concepts was both the justification and launching point for the two articles that followed. In them, we tried to build upon what had been said previously, and provide some examples of what could be accomplished through this approach.

Over the course of this series, we have explored several concepts which are building blocks for the social sciences (“normal”, “normalization”), which in turn have helped us understand and define “militarism” and “militarization”. After this, we dove into the transformative potential found within popular culture: how can it affect the people who consume it? Linking this very powerful influence to previously defined concepts was both the justification and launching point for the two articles that followed. In them, we tried to build upon what had been said previously, and provide some examples of what could be accomplished through this approach.

For this installment in the series about Pop Culture and Militarism

For this installment in the series about Pop Culture and Militarism “A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done. If a story seems moral, do not believe it. If at the end of a war story you feel uplifted, or if you feel that some small bit of rectitude has been salvaged from the larger waste, then you have been made the victim of a very old and terrible lie. There is no rectitude whatsoever. There is no virtue. As a first rule of thumb, therefore, you can tell a true war story by its absolute and uncompromising allegiance to obscenity and evil… You can tell a true war story if it embarrassses you. If you don’t care for obscenity, you don’t care for the truth; if you don’t care for the truth, watch how you vote. Send guys to war, they come home talking dirty.”

“A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done. If a story seems moral, do not believe it. If at the end of a war story you feel uplifted, or if you feel that some small bit of rectitude has been salvaged from the larger waste, then you have been made the victim of a very old and terrible lie. There is no rectitude whatsoever. There is no virtue. As a first rule of thumb, therefore, you can tell a true war story by its absolute and uncompromising allegiance to obscenity and evil… You can tell a true war story if it embarrassses you. If you don’t care for obscenity, you don’t care for the truth; if you don’t care for the truth, watch how you vote. Send guys to war, they come home talking dirty.” When President Reagan described the Soviet Union as the ‘evil empire’ in 1983, commentators were swift to detect thinly disguised parallels with the Star Wars franchise....Reagan’s dress, speech and demeanor were attuned and attentive to popular cultural references. He dressed and acted the part of statesman, cowboy, commander in chief and folksy everyday man. He quoted lines from Clint Eastwood movies and other films, including Rambo: First Blood (1982).

When President Reagan described the Soviet Union as the ‘evil empire’ in 1983, commentators were swift to detect thinly disguised parallels with the Star Wars franchise....Reagan’s dress, speech and demeanor were attuned and attentive to popular cultural references. He dressed and acted the part of statesman, cowboy, commander in chief and folksy everyday man. He quoted lines from Clint Eastwood movies and other films, including Rambo: First Blood (1982).  In Full Metal Jacket, Sergent Hartman dies at the hands of his own creation, the tormented Private Pyle, who then goes on to kill himself. It is not painted heroically, necessary, borne out of duty. It is, however, a direct result of Hartman’s teachings, and he dies proud of the killer he created. Ultimately, "rather than being moulded into an efficient and noble group of all-American boys by a harsh but decent sergeant, the recruits have their humanity stripped away in horrifying fashion. "

In Full Metal Jacket, Sergent Hartman dies at the hands of his own creation, the tormented Private Pyle, who then goes on to kill himself. It is not painted heroically, necessary, borne out of duty. It is, however, a direct result of Hartman’s teachings, and he dies proud of the killer he created. Ultimately, "rather than being moulded into an efficient and noble group of all-American boys by a harsh but decent sergeant, the recruits have their humanity stripped away in horrifying fashion. " Can seemingly innocuous activities such as playing video games, watching movies, or binging on TV shows affect your ways to see the world or how you behave? Could it affect social norms? Is one able to “turn one’s brain off”, and not be affected beyond the most superficial level, by what one is consuming? Much has been written about violence in the media and how it might affect people’s behavior, and indeed, positive correlations with violence can be found

Can seemingly innocuous activities such as playing video games, watching movies, or binging on TV shows affect your ways to see the world or how you behave? Could it affect social norms? Is one able to “turn one’s brain off”, and not be affected beyond the most superficial level, by what one is consuming? Much has been written about violence in the media and how it might affect people’s behavior, and indeed, positive correlations with violence can be found In the previous articles, we talked about how normal is defined differently in both space and time; just as Japan and Argentina might have two different ideas of what constitutes as “normal”, so does 18th century and 21st century United States. We also talked about normalization, or how things become more (or less) socially accepted over time. Finally, we introduced the concept of “militarism”. In this article, we’ll attempt to define it as concisely as possible, as well as give examples of militarism in Japan.

In the previous articles, we talked about how normal is defined differently in both space and time; just as Japan and Argentina might have two different ideas of what constitutes as “normal”, so does 18th century and 21st century United States. We also talked about normalization, or how things become more (or less) socially accepted over time. Finally, we introduced the concept of “militarism”. In this article, we’ll attempt to define it as concisely as possible, as well as give examples of militarism in Japan.

Last article, we tried to answer the question of “what is normal?” and after a few examples, eventually settled on “normal is what a group of people are used to.” In this article, we’ll look at an example of the ‘normalization’ process, that is, getting used to something to the point where alternatives are forgotten. We’ll conclude by introducing the main topic of this series: how the presence of the United States military in a surprising amount of aspects of American culture has become so normal that it is no longer noticed or questioned.

Last article, we tried to answer the question of “what is normal?” and after a few examples, eventually settled on “normal is what a group of people are used to.” In this article, we’ll look at an example of the ‘normalization’ process, that is, getting used to something to the point where alternatives are forgotten. We’ll conclude by introducing the main topic of this series: how the presence of the United States military in a surprising amount of aspects of American culture has become so normal that it is no longer noticed or questioned.