Arecibo, Puerto Rico August 20, 2023 Statement: Young veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, who suffers from his mental faculties due to his incursion into the wars, is accused of taking his father's life in events that occurred in May , 2022

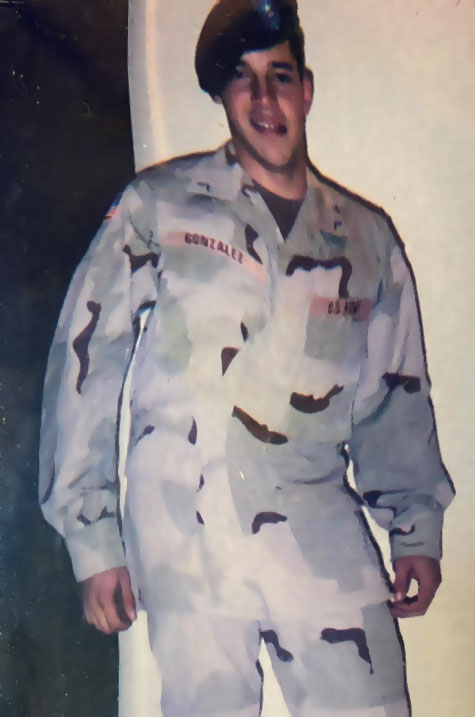

August 08, 2023 / Sonia Santiago Hernández / Mothers Against the War - Christian González Martell is a 39-year-old Puerto Rican young man, a veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who deprived his father of his life on May 30, 2022 during a psychotic episode. . At the first hearing on September 14, the judge determined that he was not prosecutable at the time. Despite this, he has been subjected to several hearings in court. His trial will begin on September 21st.

August 08, 2023 / Sonia Santiago Hernández / Mothers Against the War - Christian González Martell is a 39-year-old Puerto Rican young man, a veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who deprived his father of his life on May 30, 2022 during a psychotic episode. . At the first hearing on September 14, the judge determined that he was not prosecutable at the time. Despite this, he has been subjected to several hearings in court. His trial will begin on September 21st.

His family had tried to get him treated at the Veterans Hospital in Rio Piedras upon his return from the military.. His mother, Romilda Martell, tells us that Christian has multiple mental health diagnoses: schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress syndrome and others, result of his participation in wars. The treatment of him at the Veterans Administration was substandard and irresponsible. They only assisted him sporadically and virtually. He exhibited extreme paranoid behavior, poor judgment, hallucinations. Mrs. Martell asked for support and adequate treatment for her son, to no avail. Today she awaits trial for murder.

We have several veterans incarcerated: Orlando Rivera, a veteran of the war in Afghanistan, in 2014 murdered 2 people on the Tuque de Ponce beach, while he was jogging. Doña Carmen Delgado was one of the victims. As she opened an umbrella , he murdered her with a pistol and continued jogging..His family had taken him to the Veterans Hospital on several occasions. They told him that there were no psychiatric beds and that he should go to a civilian hospital. Soldiers and veterans are prohibited from talking about war actions. It is difficult for them to receive therapies in civilian clinics... The Veterans Hospital did not follow up. He was sentenced to 97 years in prison.

Esteban Santiago, a young Puerto Rican veteran, is imprisoned for life in a jail in Florida. He murdered 5 people at the Ft. Lauderdale airport

in 2017. His family had taken him to receive treatment at the Veterans Hospital in PR when they noticed his incoherent and aggressive behavior after having fought in Afghanistan. That hospital did not treat him responsibly.

Twenty veterans commit suicide daily. Forty percent of the two and a half million soldiers who have participated in the wars in Iraq or Afghanistan have a mental health diagnosis, mainly Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome.