The Following article IS A LESSON in representative clarity of US America as an unrepentant empire, with all the resulting nationalism and militarism that extends down from that and with those manifestations embraced. Invisible to most, an unobstructed view of the language of that nationalism and, by the nature of this beast, the foundation of all permanent war.

And the remorse of a vision unfulfilled!

- NNOMY

10/19/2021 / Wes O'Donnell / Managing Editor, Edge. Veteran, U.S. Army & U.S. Air Force - If we don’t figure out why soon, it will become a national security crisis.

10/19/2021 / Wes O'Donnell / Managing Editor, Edge. Veteran, U.S. Army & U.S. Air Force - If we don’t figure out why soon, it will become a national security crisis.

Movies have always had an unhealthy influence on me. I came of age in Ronald Reagan’s neon-tinted 1980s, complete with big hair and big action heroes. My role models were people like Arnold Schwarzenegger in Commando, Sylvester Stallone in Rambo, and Carl Weathers in Predator.

Even James Cameron’s Colonial Marines from 1986’s Aliens made militarism cool well before the word “tacticool” (a portmanteau of tactical and cool) was invented in 2004.

These over-the-top action heroes glorified the unstoppable might of the American military; no doubt an effort to save face after the Vietnam War. Even Oliver Stone’s Platoon, arguably an anti-war movie, taught me about self-sacrifice.

For me, joining the military was a grand adventure – A hero’s journey

Joining the Army seemed like an adventure; I thought “I’ll live my action movie fantasy and get college money while I’m at it.” At that age, I didn’t give a millisecond of thought to my own mortality. After all, as 80’s action movies illustrated, bad guys have horrible aim.

When my Army recruiter in Texas used to talk about his job in artillery, his eyes sparkled. It was clear that he loved his job (or at least loved blowing things up). But my mind was firmly set on the infantry, due in part to some weird fascination with hyper-masculine men saying catchphrases and shooting bad guys from the hip.

Kids from my generation rushed into military service. Morale was high. By the mid-90s the Soviet Union had collapsed, and our military had just defeated the fifth-largest army in the world in Desert Storm. Twenty years after the end of Vietnam, America was back in the winner’s circle.

But only a shockingly small percentage of today’s young people are considering joining the military. To be clear, my generation, GEN X, was born between 1964-1981, Millennials 1981-1997, and Gen Z 1997 to present.

So, as a member of Generation X, how does my decision to join the Army, (and later the Air Force), differ from today’s youth? And what’s stopping them from considering the military as a viable career option, or at least considering the military as a transition between high school and college?

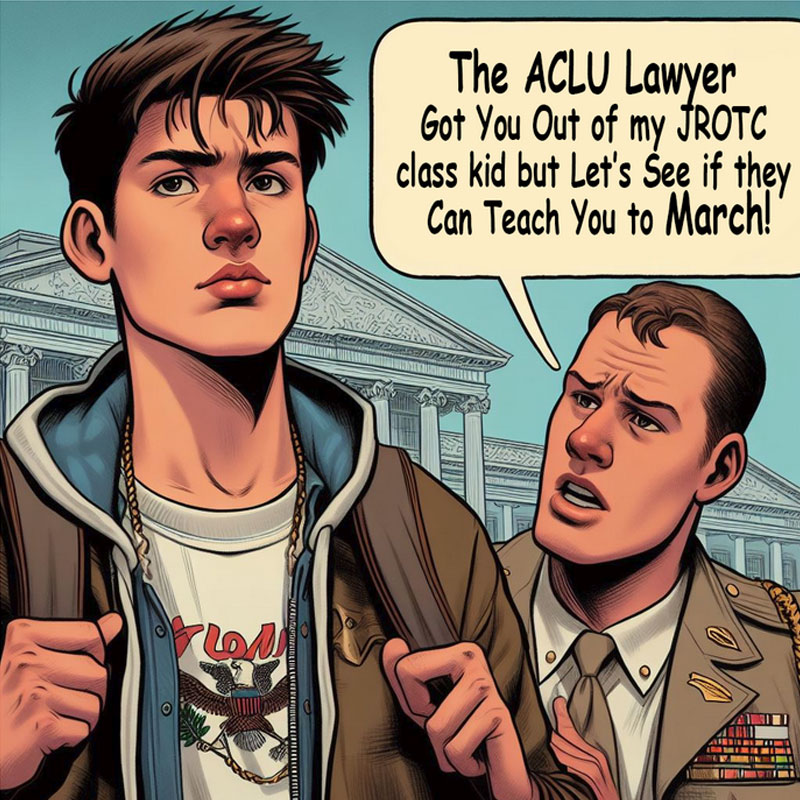

3/25/2024 / Gary Ghirardi & Copilot Ai / NNOMY - The Microsoft Copilot online artificial intelligence program was utilized to write a story based on three requests; to not be placed into the high school based Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps program from a students objection, a parental objection, and finally a legal challenge in court with the plaintiff represented by the American Civil Liberties Union. The outcomes are curious in that they appear to reflect some kind of conditioned learning on the part of the Copilot program that favors the military all the way up to a legal challenge.

3/25/2024 / Gary Ghirardi & Copilot Ai / NNOMY - The Microsoft Copilot online artificial intelligence program was utilized to write a story based on three requests; to not be placed into the high school based Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps program from a students objection, a parental objection, and finally a legal challenge in court with the plaintiff represented by the American Civil Liberties Union. The outcomes are curious in that they appear to reflect some kind of conditioned learning on the part of the Copilot program that favors the military all the way up to a legal challenge.

10/19/2021 / Wes O'Donnell / Managing Editor,

10/19/2021 / Wes O'Donnell / Managing Editor,