Kenneth J. Saltman -

Recently, critics of school commercialism such as Alex Molnar and the Commercialism in Education Research Unit that he directs as well as the U.S. Surgeon General have taken note of just how fat U.S. students are getting. For Molnar, who is one of the nation’s most prominent critics of school commercialism and other authors on his site (http://www.schoolcommercialism.org), childhood obesity must be understood in relation to the deluge of junk food marketing aimed at children and infiltrating schools (See Mission: Readiness). The goal of these authors is to get the marketers and profiteers out of the schools. For the U.S. Surgeon General, the goal is somewhat different. Addressing the largest ever conference on childhood obesity in San Diego attended by Doctors, educators, and parents, Surgeon General Dr. Richard Carmona was quoted in the San Fransisco Chronicle,

Recently, critics of school commercialism such as Alex Molnar and the Commercialism in Education Research Unit that he directs as well as the U.S. Surgeon General have taken note of just how fat U.S. students are getting. For Molnar, who is one of the nation’s most prominent critics of school commercialism and other authors on his site (http://www.schoolcommercialism.org), childhood obesity must be understood in relation to the deluge of junk food marketing aimed at children and infiltrating schools (See Mission: Readiness). The goal of these authors is to get the marketers and profiteers out of the schools. For the U.S. Surgeon General, the goal is somewhat different. Addressing the largest ever conference on childhood obesity in San Diego attended by Doctors, educators, and parents, Surgeon General Dr. Richard Carmona was quoted in the San Fransisco Chronicle,

"Our preparedness as a nation depends on our health as individuals," he said, noting that he had spent some of his first months in office working with military leaders concerned about obesity and lack of fitness among America's youth. "The military needs healthy recruits," he said. (Severson, p. 1)

The article noted that Carmona was careful not to assail the junk food industry for its part in threatening the national defense by flabbifying the nation’s chubby little defenders.

While the critics of school commercialism are correct to criticize the role of marketers of junk food for their part in commodifying every private and public space with health-harming products and slick advertisements for them, I want to focus here on theincreasing prominence of the discourse of security as it appears to influence educational policy and school culture but also participates in fostering the neoliberal agenda.

Military generals running schools, students in uniforms, metal detectors, police presence, high tech ID card dogtags, realtime internet-based surveillance cameras, mobile hidden surveillance cameras, police presence, security consultants, chainlink fences, surprise searches – as U.S. public schools invest in record levels of school security apparatus they increasingly resemble the military and prisons.

Militarized schooling in America can be understood in at least two broad ways: 1) “military education”, and 2) what I am calling “education as enforcement.” Military education refers to explicit efforts to expand and legitimate military training in public schooling. These sorts of programs are exemplified by JROTC (Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps) programs, the Troops to Teachers program that places retired soldiers in schools, the trend of military generals hired as school superintendents or CEOs, the uniform movement, the Lockheed-Martin corporation’s public school in Georgia, and the Army’s development of the biggest online education program in the world as a recruiting inducement. Military education seeks to promote military recruitment as in the case of the 200,000 students in 1420 JROTC Army programs nationwide. These programs parallel the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts by turning hierarchical organization, competition, group cohesion, and weaponry into fun and games. Focusing on adventure activities these programs are extremely successful as half (47%) of JROTC graduates enter military service. What I am calling “Education as Enforcement” understands militarized public schooling as part of the militarization of civil society that in turn needs to be understood as part of the broader social, cultural, and economic movement for corporate globalization that seeks to erode public democratic power and expand and enforce corporate power locally, nationally, and globally, what Ellen Meiskins Wood calls “the New Imperialism” that seeks to control markets everywhere and all the time. In this sense the Bush administration’s new doctrine of permanent war is a more overt expression of corporate globalization, which should be viewed as a doctrine rather than as an inevitable phenomenon is driven by the ideology of neoliberalism.

In what follows I show how the discourse of security is being used to unite educational policy reform with other U.S. foreign and domestic policies that foster repression and the amassing of corporate wealth and power at the expense of democracy. I identify a number of different meanings of security: students are being turned into securities in the sense of commodities; students are being made into securities in the form of investment opportunities; students are being increasingly subjected to repressive security apparatus in the form of zero tolerance policies, surveillance, searches, and police presence; students are being made less secure by the continuation of neoliberal policies that gut the caregiving and social support role of the public sphere; finally, as the above example of the flabby defenders and other examples below illustrate, students are being increasingly defined by their future capacities to serve the nation’s military as it takes on a more overt imperial mission and continues the state of permanent war begun with the “war on terror.” 2 I conclude by discussing the rise of student resistance that links the challenge to educational policy to the challenge to US foreign and domestic policy.

As this article goes to press the New York Times framed the U.S. Supreme court case over affirmative action at the University of Michigan on the pragmatic grounds of national security rather than ethical grounds of racial equity (Greenhouse, 2003). The Times frames the educational institution as a military training ground. Military officers submitted briefs to the court supporting educational affirmative action as serving the interests of military academies and troops in the field. Education has been increasingly defined as a national security issue even prior to the advent of the “war on terror.” In 2000 the U.S. Commission on National Security, also known as the Hart-Rudman Commission, affirmed the national security role of public schooling openly declared in 1983 by A Nation at Risk, “If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war.” Education has been defined through the discourse of national security from the Cold War to the rise of neoliberalism with the end of the Cold War, to the Hart-Rudman U.S. Commission on National Security in 2000, to the "No Child Left Behind" legislation and the state department's anti-terrorism pedagogy following 9/11. The defining of public schooling through national security has consistently been a matter of subjugating the democratic possibilities of public education to the material and cultural interests of an economic elite. Hart-Rudman made this quite explicit, calling for increased attention to the role of education for national security by suggesting an increased role of the private sector and making explicit that although labor and environmental concerns should be considered, they should not be allowed to block or reverse free-trade policy. However, the ways that public schooling has been defined through national security has changed markedly in particular with regard to the rising culture of militarism of which the newest incarnation participates. Current attempts to redefine public schooling as a security matter participate in the broader attack on public space and public participation as corporate media propagates an individualizing culture of fear. The importance of highlighting these changes involves both challenging the idea that new militaristic school reform initiatives are merely a response to 9/11 and more importantly providing the groundwork to challenge the ways that education for national security undermines the democratic possibilities of public schooling and the public sector more broadly.

The Securitized Student: Making Kids into Securities, Making Kids Insecure

The neoliberal ideal of making an enterprise of oneself is tied to the dismantling of the security of state provisions for kids.3 Put another way, the entrepreneurial self championed by neoliberal ideology supports and is supported by the undermining of social, that is, collective security by shifting security to the individual. Educational reforms of the late nineties and early 00’s share the same goals as that of Welfare to Workfare. The rise of homelessness resulting from the dismantling of welfare has fallen hardest on children. The average age of a homeless person in America is nine years old. The undermining of social forms of security takes shape in the attempts to privatize the social security program, the continued privatization of public schools, the discursive framing in corporate media of the public good as the private accumulation of profit and the health of the stock market. In what Zygmunt Bauman refers to as the “individualized society” (2001) politics is rendered at best a privatized affair and at worst impossible. Moreover, as Bauman points out, neoliberalism results in the privatization of the means of collective security.

Bauman suggests that corporate globalization (the global neoliberal agenda) with its unchecked liberalization of trade, privatization of public services, “flexible” labor, and capital in constant flight renders individuals in a state of constant insecurity about the future (Bauman, 1998; Bauman, 1999). For Bauman, the possibility of the kind of political struggle that could expand democratic public values and would provide the necessary solidarity that forms the pre-conditions of social security has been imperiled by such a thorough commodification of social life that even thinking the public, let alone working to strengthen it, has become difficult. Mass-mediated representations found in such varied locations as on nightly news and marginal sports, translate economic insecurity into privatized concerns with public safety such as street crime, school dangers, viruses, and, of course, terrorism. As well, mass media channels this anxiety into private preoccupations with controlling and ordering the body, its fitness, its appearance, its fluids, pressure, caloric intake. Both the material and representational assault on the public sphere produce anxiety, insecurity, and uncertainty about a future filled with flexible labor, capital flight, and political cynicism. The dismantling of social safety nets and other public infrastructure (such as social security, public schools and universities, welfare, public transportation, social services, healthcare, public legal defense, public parks, and public support for the arts) intensifies and accelerates this insecurity. The widespread insecurity resulting from the dismantling of the public sector undermines the kind of collective action that could address the very causes of insecurity.4 As Bauman insightfully writes,

The need for global action tends to disappear from public view, and the persisting anxiety, which the free-floating global powers give rise to in ever growing quantity and in more vicious varieties, does not spell its re-entry into the public agenda. Once that anxiety has been diverted into the demand to lock the doors and shut the windows, to install a computer checking system at the border posts, electronic surveillance in prisons, vigilante patrols in the streets and burglar alarms in the homes, the chances of getting to the roots of insecurity and control the forces that feed it are all but evaporating. Attention focused on the ‘defence of community’ makes the global flow of power freer than ever before. The less constrained that flow is, the deeper becomes the feeling of insecurity. The more overwhelming is the sense of insecurity, the more intense grows the 'parochial spirit.' The more obsessive becomes the defence of community prompted by that spirit, the freer is the flow of global powers... And so on. (Bauman, 1999: 195-196)

What Bauman identifies as a snowball effect of privatizing and individualizing logic that further undermines collective political action to alleviate the sources of insecurity is exemplified by such incidents as 1) the rise of domestic militarization in schools post-Columbine, 2) Sun Trust Equities publishing a report to investors with a title “At-Risk Youth--A Growth Industry,” 3) the U.S. Surgeon General declaring that obesity in schoolchildren is a threat to national security because kids will be unfit to later become soldiers, 4) a company called My Rich Uncle that offers investors an opportunity to speculate on the future earnings of students by lending them money for university and then later collecting a percentage of their income, 5) the provision in No Child Left Behind that requires student information to be used for military recruitment purposes. In what follows I use some of these events to elaborate on the different political uses of the discourse of security on students and in schools.

Security I: The Political Use of Security Apparatus on Youth

The individual student in U.S. public schools is increasingly being subject to intensified security apparatus. In this first sense of the term security refers to coercive measures that are justified on the grounds of the protection of youth. These measures such as zero tolerance policies, surveillance, uniforms, and police presence participate in redefining youth as simultaneously culpable for social problems while undermining the possibilities of youth agency (Giroux, 1997). Such school reforms participate in the broader move to legislate and publicize youth as the cause of social problems through, for example, trying children as adults in criminal court, blaming kids for crime, poverty, sexual promiscuity, unwed pregnancy, and consumerism (Giroux, 2001; Males, 1998, 1996). At the same time, youth are discouraged from acting as political agents through institutional and discursive regulation that takes the form of infantalizing youth in mass media and school curricula--that is, they are discouraged from 1) understanding how their actions participate in larger social, political, cultural and economic formations that have a bearing on their own lives and the lives of others and 2) they are discouraged from having a sense of the possibility of acting on such knowledge to transform those conditions.

An important dimension to this aspect of security is the way that it links into the racialized discourse of discipline. Prior to Columbine a politics of containment was largely reserved for predominantly non-white urban public schools while mostly white suburban schools have been viewed as worthy of investment in educational resources. Treated as containment centers, urban public schools in the U.S. do not receive the kinds of resources that suburban schools receive. They do, however, receive strict disciplinary measures for low performance after having been deprived of resources such as books, adequate numbers of teachers and administrators and physical sites. Such punitive measures include remedial teacher training in which teachers are forced to follow strict guidelines for curriculum content and instructional method. And of course U.S. public schools are not only subjected to scripted lessons but the growing calls for such discipline-oriented accountability schemes as high stakes testing, remediation and probation for schools and teachers that do not meet the scores, standardized curriculum, etc. These discipline-oriented reforms and discipline-based language which are widely promoted across the political spectrum shift the focus and blame for a radically unjust system of allocation onto students, teachers, and administrators who appear to lack the necessary discipline for success and they shift the focus and blame away from the conditions that produce a highly unequal system of public education. When market enthusiasts refer to the “failure” of the public schools, they are talking about urban largely non-white public schools that are deprived of adequate resources and located in neighborhoods that have been subject to capital flight and systematic disinvestment and not about the suburban, largely white, professional class schools that are glaring successes with massive resources, small class sizes, and communities that have employment and infrastructure. Just as the highly racialized broader public discourse of discipline functions politically and pedagogically to explain social failings as racial and ethnic group pathologies that have infected individuals with sloth, mass media and educational reformers extend the discourse of discipline to explain away unequal allocations of resources to schools as the individual behavioral failings of students, teachers, and administrators. Moreover, the discourse of discipline shuts down any kind of discussion of whose knowledge and culture is taught in schools and valued in society.

Security II: At-Risk Youth--A Growth Industry

Students are not only being subject to disciplinary security, they are also being transformed into securities. This sense of security refers to the ways that students are being viewed as investment opportunities by the financial sector. In 1998 SunTrust Equitable Services investment company issued a report to investors about the investment potential of for-profit services for “at risk” youth. The report was titled, “At-Risk Youth…a Growth Industry.”

As Betty Reid Mandell, among others, points out, millions of youth, who were the primary recipients of welfare, are the prime victims of its dismantling. Their increasingly at-risk status transforms youth into commodities in a $21 billion for-profit service market…Who are these for-profits who have scored on the dismantling of social services for youth? One of the biggest poverty profiteers is big three military contractor Lockheed Martin, which is operating welfare-to-work schemes in four states. For-profit Youth Services International, purchased in 1998 by Correctional Services Corporation, makes over $100 million a year running juvenile detention “boot camps,” subjecting youth to physically demanding military training…What is particularly egregious about these examples is that after youth have been put “at risk” by the denial of public services, such as the late AFDC, they then become an investment for the same people who lobbied for the destruction of the same public services that were designed, when properly supported, to keep youth out of risk. (Saltman, 2000)

These examples of how the military and prison industries are investing in the undermining of security for youth demonstrates that the disciplinary form of security is deeply interwoven with the financial form of security in which students are made into investments in part through the undermining of caregiving forms of security.

Security III: The Student as Commodity

A new company called My Rich Uncle facilitates high school and University students loans from investors. The investors essentially speculate on whether or not the students will have lucrative careers after school and lend students tuition in exchange for a percentage of future earnings--between 1% and 8% of the student’s future gross income. The website (http://www.myrichuncle.com) states:

MyRichUncle allows students and parents to confidently confront the financial challenges of paying for higher education.

Again from the website:

Rather than provide students with loans where students are obligated to pay the lender the principle amount plus interest, Khan and Garg wanted to provide students with Education Investments. That is, kids could receive the funds they needed for school from investors, and would only be obligated to pay a fixed percentage of their income for a fixed period of time. In effect they would pay more when they had more and less when they had less. At the end of the period their obligation is over even if the cumulative amount they had paid was less than the amount they initially received in financing. The idea is to let investors share in the student’s return on investment in education.

Both the company and National Public Radio (Horsley, 2003) remind us that a college degree doubles the lifetime earning potential of an individual. Michael Robertson, founder of mp3.com, and an investor in MyRichUncle stated in the NPR report that, “an education is one of the best investments you can make” and there has “never been a way to invest in young people and capture that growth.” In the same report Sandra Bahm refers to the company and the concept as a new kind of sharecropping. Says one of the co-founders of the business, the company is “one of those cases in which greed and altruism work really well together.”

The business can only be understood in relation to the failure of the U.S. to provide universal higher education. The state failure to provide educational and labor security results in privatized forms of security such as this one. Part of the problem with the concept is the way it participates in the neoliberal vision of education as principally of value for its economic exchange capacity. Within this perspective the value of schooling is individually conceived of through individual upward social mobility and nationally in terms of global economic competition. The neoliberal discourse of human capital naturalizes these ideas of education as principally a market and the student as yet another commodity and investment opportunity. For example, The Cato Institute’s journal Policy Analysis put out a study of these so-called “Equity-like” Instruments for Financing Higher Education, evaluating them on economic grounds and affirming higher education as a for-profit endeavor and an economic investment best served through competition by investors to hold student debt.

Human capital contracts are equity-like instruments because the investor’s return will depend on the earnings of the student, not on a predefined interest rate. The effects of these arrangements are, among others, less risk for the student, transfer of risk to a party that can manage it better, increased information regarding the economic value of education, and increased competition in the higher education market. (Palacios, p. 1)

In addition to the ways the company transforms students into commodities and imagines schooling as principally a business, one aspect of this speculation that has gone relatively undiscussed in the literature is the social implications of investors wanting to put their money towards principally lucrative degrees such as business, law, engineering, and sciences and shying away from the humanities, social sciences, and arts. Another is the inevitable desire among investors to want to avoid investing in women who will be far more statistically likely to take maternity leave from work at some point within the ten years after graduation. The less lucrative a future field is the higher the interest rates. Meaning that the less a student will earn in the future the more he will have to pay for his loan. Ultimately, with this form of financing higher education the funding system is more deeply involved in placing value on different fields at an earlier stage in an individual’s trajectory through the field, on the career path. Ironically, the financial literature refers to this as an “Equity-like” Instrument. That’s right, it is kind of like equity but highly inequitable. Furthermore, MyRichUncle transforms philanthropy into investment opportunity and poverty into a commodity.

This aspect of the securitization of students concerns the transformation of the student into a commodity in which to speculate. Part of what is radical is that individual virtue is tied to the capacity to sell oneself, thereby giving a guise of increased individual autonomy that is only expressible through the market. So while responsibility for funding education in a way that gives individuals full control over their course of study is radically individualized through the skyrocketing costs of higher education, at the same time the range of choices in the student’s future pursuits are limited by the speculative value of the choice. Consequently, poorer students have fewer choices than wealthier ones.

5.5 The case of My Rich Uncle is similar to that of two high school students who sold themselves as human billboards to FirstUSA credit card company in exchange for college tuition. The neoliberal ideal of making an enterprise of oneself is tied to the dismantling of the security of state provisions for kids. The entrepreneurial self championed by neoliberal ideology supports and is supported by the undermining of social, that is, collective security by shifting security to the moral responsibility of the individual.

Security IV: The Student as Weapon, The Student as Soldier

Consider the testimony of Paul Vallas to the U. S. Congressional Committee on Education and the Workforce. Vallas is an accountant and former “CEO” of Chicago Public Schools and current “CEO” of Philadelphia Public Schools, which has class and race demographics similar to Chicago.

To assist teachers in teaching to the standards, we have developed curriculum frameworks, programs of study, and curriculum models with daily lessons. These materials are based on training models designed by the Military Command and General Staff Council…Increasingly, we have built collaborative relationships with the private sector. (Vallas, 2001)

While Vallas makes quite explicit that the model for his reforms are the military’s training methods and his background in accounting, he does not address the role of such rigid and authoritarian methods in a democratic nation. Is democracy about nothing more than individuals competing against each other for test scores? For prestigious degrees? For jobs? For consumer goods? Unfortunately, to too great an extent, it is presently. However, it doesn’t have to be. Democracy can also be about collaboration, collective action, and a different kind of competition that fights for social justice rather than individual advancement--the well-being of all rather than the ascendancy of one.

Vallas’ perspective is consistent with the re-authorized Elementary and Secondary Education Act (Bush’s No Child Left Behind) that was widely supported across party lines. A central aspect of No Child Left Behind (aptly titled with a military metaphor referencing Vietnam-era troop recovery) is defining educational accountability through testing which is a boon for the corporate testing and textbook publishing companies such as big three McGraw-Hill, Houghton Mifflin, and Harcourt General. No Child Left Behind makes states create performance-based achievement measures that must be met within a specific time frame. When those goals are not met, states will be required to spend public money on remediation. Much of this will be a boon for private for-profit test companies, educational publishers, and for-profit consulting companies. In his article in The Nation “Reading Between the Lines” Stephen Metcalf shows how the “scientific” standards of No Child Left Behind were created by the same companies lined up to do remediation such as McGraw-Hill.

The Bush legislation has ardent supporters in the testing and textbook publishing industries. Only days after the 2000 election, an executive for publishing giant NCS Pearson addressed a Waldorf ballroom filled with Wall Street Analysts. According to Education Week, the executive displayed a quote from President-elect Bush calling for state testing and school-by-school report cards, and announced, "This almost reads like our business plan."

Remediation by test companies and educational publishers means that this "accountability" based reform was in large part set up as a way for these testing and publishing companies to profit by getting federally-mandated and state-mandated business. The market ideal of "competition" driving testing-based reform could not be farther from the lack of market competition in the state and corporate practice of setting up these reforms through the kind of crony capitalism Metcalfe details.

These ever more frequent tests which largely measure socially-valued knowledge and cultural capital (most of which students learn at home and in their social class milieu) will be used to justify remediation by states and locales. 5 The federal government will insist that test scores be improved by 1) either allowing students to go to other schools or 2) by using public money for remediation efforts. The courts have already determined that the federal government will not enforce at the local level the freedom of students to go to better schools. So the remediation route is the one that is going to be the biggest result of No Child Left Behind. As a result for-profit education companies are going to cash in on this with terribly un-progressive pedagogical methods that aim to deskill and deintellectualize teaching through tactics like scripted lessons in those places hardest hit by the results of corporate lobbying to evade taxes and where neoliberal reforms have allowed capital flight to leave communities with no employment.

The threat posed by neoliberal reforms exemplified by Vallas, No Child Left Behind, and McGraw-Hill should not be understood as primarily or exclusively a threat to progressive pedagogical methods. The fact is, there are in evidence many corporate-produced and corporate-administered curricula that are methodologically progressive such as Disney’s Celebration Schools that cater to professional class kids as well as, for example, some of what the oil companies dump on schools. 6 Here, the distinction between critical thinking skills (called for by liberal critics of corporate school initiatives) and critical pedagogy really matters. Much corporate-produced curriculum does emphasize knowledge that is “meaningful” to students, “collaborative,” and “student-centered.” These can all be part of a very conservative curriculum that does not address the socio-political realities informing the production of knowledge that involves relating knowledge to the interlocking systems of capitalism, White supremacy, and patriarchy as well as to many other critical relationships such as those between knowledge and pedagogical authority, ethics, and identity formation.

Stephen Metcalfe makes fantastic criticism of crony capitalism between McGraw-Hill and three generations of Bushes. However, he misses the chance to explore the implications of how John Negroponte, who left McGraw-Hill to become U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and a leading figure in the “War on Terrorism,” participated in the 1980s in what are regarded in the international community as crimes against humanity and U.S. state-backed terrorism in Honduras. 7 It is imperative that future work on corporatization of schools consider the relationship between the disciplining of particular populations in the U.S. through the mechanisms of capitalist schooling and how this relates to the disciplining of populations in other nations through both direct coercion and the production of consent that is largely accomplished through cultural production. It is also time for the global dynamics of discipline to be understood in relation to how the discourse of discipline, drawn from the market-based metaphor of “fiscal discipline” and the military ideal of physical and behavioral discipline, is the basis for the most recent educational reforms.

Some of the more critical approaches to criticizing corporate involvement in schools link corporate initiatives and their aforementioned effects to much broader social issues and most centrally the concerted efforts by corporations in conjunction with states to expand their power locally, nationally, and internationally. This can be found in the work of scholars such as Michael Apple, Ramin Farahmandpur, David Gabbard, Henry Giroux, Robin Truth Goodman, Don Trent Jacobs, Pepi Leistyna, Pauline Lipman, Donaldo Macedo, Peter McLaren, and E. Wayne Ross among others. This broader approach recognizes that corporations know just how much knowledge, schooling, and education more generally matter in the exercise of power. Knowledge, schooling, and education broadly conceived matter to corporations to frame events, construct meanings, and disseminate values in ways favorable to corporate financial and ideological interests. In this larger formulation, it becomes difficult not to make the links between, say, when a company such as Amoco (now BPAmoco) in conjunction with Scholastic, Waste Management, and public television freely distributes middle school science curriculum in Chicago Public Schools portraying the earth under benevolent corporate management when that curriculum fails to mention domestic pollution that has resulted in vast environmental devastation and cancer in entire neighborhoods in the mid-west, the spilling of millions of barrels of oil in pristine Alaskan artic land, the defiance of government orders to stop spilling, the involvement of the company in the murderous actions of right-wing paramilitaries in Colombia, or how BPAmoco and other oil companies will benefit from the U.S. waging war on states with great oil reserves. Chevron, involved in helicopter gunship attacks on protesters in Nigeria, is quite clear on what is at stake in the battle over who controls knowledge: “We are,” they write, “a learning company.”

Sadly, few of the critics of corporate involvement in schools have made such links. Critics of school commercialism, public school privatization and all the varieties it takes should be concerned with the threats to the global public posed by the expansion of corporate power over meaning-making technologies that include not just schools but mass media as well. As the United States takes on an increasingly open imperial mission in defiance of the international community and intensifies domestic militarization, it becomes clear that George W. Bush’s ultimatum following September 11 about other states being either “with us or against us” increasingly applies to the ethical and political positions that educators must take. The battle lines for educators, however, should not be drawn the way Bush would have it--between a jingoistic unquestioning nationalism versus a treasonous questioning of the motives of the state. Rather, ideally the battle lines for educators are over, on the one hand, the expansion of public control over not just knowledge and foreign and domestic policy but also the meaning and future of work, leisure, consumption, and culture. On the other side of the battle lines is the state-backed intensification of corporate control over knowledge, foreign and domestic policy, work, leisure, consumption, and culture simultaneous with the continued diminishment of public control. The repressive elements of the state in the form of such phenomena as the suspension of civil liberties under the USA Patriot Act, militarized policing, the radical growth of the prison system, and intensified surveillance accompany the increasing corporate control of daily life. The corporatization of the everyday is characterized by the corporate domination of information production and distribution in the form of control over mass media and educational publishing, the corporate-use of information technologies in the form of consumer identity profiling by marketing and credit card companies, and the increasing corporate involvement in public schooling and higher education at multiple levels.

By remaining focused on pedagogical methods, the threat of an abstract notion of “quality education”, and pretending that if commercialism can be fended off it will allow students the benefits of a neutral education, liberal critics 8 of the corporate assault on public schooling miss the extent to which the entire school curriculum is wrapped up with both material and symbolic power struggles or cultural politics--that is, the struggle over values, meanings, identities, and signifying practices. 9

The deep structural ways that schools function in the interests of capital complicates the common sense revulsion that most people feel about school commercialism--a common sense echoed in liberal educational policy circles that presume that everyone knows what is wrong with business getting into schools. That is, it threatens some abstract notion of a “quality” education. Despite the limitations of the model (Giroux, 1983; Aronowitz & Giroux, 1989) the insights of Bowles and Gintis from the 1970s remind us that corporate entry into schools isn’t brand new but further that it runs far deeper than the introduction of advertising and product placement in curriculum which so many liberal critics of corporatization have focused on in the past few years. 10 One of the central and best aspects of the public nature of public schooling is that in its best forms it allows for the interrogation and questioning of values and beliefs. While historically and presently too much of public schooling has followed an authoritarian model that discourages intellectual curiosity, debate, and a culture of questioning, what makes public schools special is their capacity, by virtue of their public nature, to be places where such a culture of political and ethical questioning can flourish and be developed. The same cannot be said of private for-profit schools. Disney’s Celebration School in its corporate community in Celebration, Florida, despite its progressive pedagogical methods, is not likely to encourage questioning about what part ABC Disney plays in the corporate media monopoly (Hazen & Winokur, 1996; Giroux, 2001b) or in U.S. imperialism (Dorfman & Mattelart, 1991) or about the intensifying corporate control over information production and meaning-making more generally that spans mass media and schooling. There are, of course, countless examples of public schools that do demonstrate democratic culture. However, most of the reforms tied to No Child Left Behind do not foster such a culture that makes questioning power central. Rather it deepens and expands authoritarian values, counters teaching as an intellectual endeavor, and by standardizing curriculum and employing discipline-based remediation it simultaneously inhibits the critical engagement with knowledge and turns to the corporate sector to use tests, scripts, and prepackaged curriculum to drill knowledge into kids. (Mathison & Ross, 2002) The instrumentalism of the standards-based reform movement is inseparable from the corporate logic infecting education. 11 The same neoliberal ideology that aims to privatize and commercialize schools to teach students to make an enterprise of themselves, is the same neoliberal ideology that has dismantled welfare and gutted and privatized social services domestically and is the same neoliberal ideology that uses state resources to invest in disciplinary tactics throughout civil society and it is the same neoliberal ideology that the government exports through the threats of military and economic revenge. 12

Recently, I heard the successor to Paul Vallas, Arne Duncan, the “CEO” of Chicago Public Schools mention that roughly 90% of the students in Chicago come from families living below the poverty line and that 90% are also non-White. The structural analysis, typified by Bowles and Gintis above, undermines the liberal and conservative fiction of the innocence of the school as a space outside of the relations of capital that only gets tainted with the most explicit entry of business. One of the important tasks for critics of the neoliberal assault on schooling to comprehend now is how the reproduction of the conditions of production is shifting from an industrial to a service model in some places and in others shifting from an industrial to a prison/military model. This means that privileged largely white schools are being remade on the model of corporate culture with the goal of training future managers and consumers in a service economy while the public schools serving economically redundant working class and poor segments of the population are being increasingly given discipline in schools. The meritocratic ideal structuring educational discourse and policy debate is both itself an example of capitalist ideology structuring schools and a gross distortion of the continuing realities of the oppressive function schools serve. Such educational reform efforts concerned with, for example, individual “resilience” are grounded on lies of equal opportunity and mobility and they individualize the systemic nature of how schools further the interests of power. This should not be read as an attack on public schools (though it is a call for rejecting the plethora of garbage educational research that simultaneously affirms and effaces the oppressive function of schools) but rather a call for honesty about what schools really do as the first step for planning the remaking of schools into places where democratic cultures flourish and students can learn to imagine human possibilities beyond the market. Some students are leading the way in resisting neoliberalism and imagining the school as a place for democratic culture to be built through struggles for collective security rather than individualized forms of security. And some students are taking great risks to do so.

Heroic Students Defying Risk

Alissa Quart in her book Branded: The Buying and Selling of Teenagers extensively illustrates the teen marketing phenomenon of trendspotters and insiders in privileged schools and milieus. Fashion, clothing, accessory, and cosmetic companies and the advertising and marketing companies that work for them hire teen girl spies to spot fashion trends and to offer advice on what products fashion companies should manufacture and promote. The teens are paid less in cash and more in inexpensive promotional gimmicks and through the idea that this is training for future work in these industries. Quart estimates that there are about 10,000 teens working as fashion spies in schools. Quart paints a picture of a vicious culture of consumerism in schools that corporations promote through multiple strategies. Within the commercial culture of schools students value themselves and others through their place on the consumption hierarchy.

But as Quart points out, there are exceptions,

Katie Sierra, a fifteen-year-old tenth grader at Sissonville High School in Charleston, West Virginia, was suspended for her antiwar sentiments in October 2001. Those sentiments were expressed in a sardonic hardwritten message on her T-shirt: “When I saw the dead and dying Afghani children on TV, I felt a newly recovered sense of national security. God Bless America.” (p. 33)

Quart, despite drawing on a limited sample of upper class white students, suggests that student consumerism was only briefly interrupted by September 11 and then commodified once again through red, white, and blue sweater sets. However, it seems that Katie Sierra is not alone as student political awareness and action has been intensifying as youth identify with the political struggles for global justice, foreign debt relief, against sweatshops, against the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and against the new educational reforms such as high stakes testing. One global student protest, billed as Books Not Bombs on Wednesday March 5, 2003, drew students to the streets with slogans, signs, and chants as well as discussion and information-sharing. The Red Streak, a new Chicago Tribune publication aiming for a younger demographic than the Tribune and modeled on British tabloid dailies, had a story with the following on its front page,

Putting aside their books to protest the potential bombing of Iraq, thousands of students at high schools and colleges across the Chicago area walked out of class Wednesday to protest the war buildup in the Persian Gulf. The students here joined tens of thousands of students at more than 300 colleges and universities nationwide, according to the National Youth and Student Peace Coalition, which helped organize the day of action. “We’re spending all this money on the war, and some schools don’t have enough money for books,” said Lucy Dale, 16, a junior at Francis Parker, who cut class to head downtown. “High schoolers will have to pay for this in the future.”(Newbart, et. al., p. 1)

Students at College of Dupage carried a mock casket draped in an American flag with the field of stars replaced with the peace symbol.

The Redeye, The Chicago Sun-Times’ competitor to the Tribune’s Red Streak, had a two page spread that included chants: “We cut school because Bush is a fool”; “I called in sick of war”; “Books not bombs”; “Stop the U.S. war machine, from Palestine to the Philippines.”

The Redeye also sensationalized the event in a cover story with a heading, “Student protesters slowed traffic in Sydney, Australia, to a crawl Wednesday.” The accompanying stylistically-pornographic photo showed three high school girls in school uniforms with their blouses raised to reveal “Make Love Not War” written across their guts. Perhaps we should understand this pornographic representation of politics by large media companies as consistent with what Bauman identifies as the channeling of public concerns into individualized cares. In this case eroticizing youth to sell papers is merged with the politics of the story. However, with youth mobilization for global justice, against the war, and against No Child Left Behind, the testing craze is not only being publicized by corporate media.

The events covered above by corporate media were the result of grassroots organizing. There are a number of organizations exemplified by Monterrey Bay Educators Against the War, Teachers for Social Justice in Chicago, or the Military Out of Our Schools campaign that bring together teachers, students, university faculty and citizens to link efforts for global justice to local school policy. They are organizing walk-outs, teach-ins, curriculum fairs, and sessions to discuss, debate, educate the public, and organize. They are challenging high-stakes testing, military recruiting in schools, and recognizing that authoritarian curriculum reforms are part of the threat to democratic and public forms of schooling that need to be understood as part of the movement for global democracy.

Conclusion

Neoliberalism as the doctrine behind global capitalism should be understood in relation to the practice of what Ellen Meiskins Wood, writing in response to the 1999 U.S.-led attack on former Yugoslavia, called the “new imperialism” that is “not just a matter of controlling particular territories. It is a matter of controlling a whole world economy and global markets, everywhere and all the time.” 13 The project of globalization again made crystal clear by Thomas L. Friedman “is our overarching national interest” and it “requires a stable power structure, and no country is more essential for this than the United States” for “[i]t has a large standing army, equipped with more aircraft carriers, advanced fighter jets, transport aircraft and nuclear weapons than ever, so that it can project more power farther than any country in the world...America excels in all the new measures of power in the era of globalization.” As Friedman explains, rallying for the “humanitarian” bombing of Kosovo, “The hidden hand of the market will never work without the hidden fist--McDonald’s cannot flourish without McDonnell Douglas, the designer of the F-15. And the hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley’s technologies is called the United States Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps.” The Bush administration’s new military policies of permanent war for the maintenance of U.S. military and economic hegemony confirm Wood’s thesis. The return to cold war levels of military spending approaching $400 billion (not including the Iraq war) with only 10-15% tied to increased anti-terrorism measures (Welna, 2002) must be understood as part of a more overt strategy of U.S. imperial expansion facilitated by skillful media spin amid post-9/11 anxiety.

I have sought to show how new aspects of neoliberalism simultaneously strengthen the repressive arm of the state while continuing to weaken the caregiving role of the state. I have illustrated how public education is increasingly defined as an issue of national security thereby justifying its continuation but on repressive grounds. Why is this? One reason has to do with the way that the drive for privatization and liberalization of trade favored by the corporate sector threatens to undermine the repressive uses of state institutions. National security is one way of fending off the impositions of global trade agreements such as the FTAA without invoking a public role of schooling. In other words, the usefulness of national security as a defense of schools as public institutions evades embracing public schools for their citizen-building capacity as institutions that foster democratic participation. Instead it affirms the dominant justification for public schooling that is consistent with neoliberal ideology--that is, upward individual economic mobility and global economic competition. Schooling for national security links to the broader discourse of security and the war on terrorism that makes schools and other public institutions into the basis for national and international community defined through personal safety thereby individualizing the public possibilities for schools. By understanding how the discourse of security unites educational policy reform with other U.S. foreign and domestic policy, it becomes possible to challenge security as it is being used to justify repressive state policy and the amassing of corporate wealth and power. One step in such a challenge is to understand why the discourse of security succeeds as widely as it does and to understand the hopeful fact that with so many students it fails. 14 In the course of critical pedagogical practice, teachers, and other cultural workers should both develop pedagogies that translate individualized insecurities into matters of public security and redefine security through its public possibilities in the form of social protections, resources, and the redistribution of deliberative power for the future of labor, healthcare, and education.

References

Aronowitz, Stanley & Giroux, Henry A. (1994). Education Still Under Siege. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Bauman, Zygmunt. (2001). The Individualized Society. Malden, MA: Polity.

Bauman, Zygmunt. (2000). Globalization: The Human Consequences. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bauman, Zygmunt. (1999). In Search of Politics. Malden, MA: Polity.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (2001). In the documentary film Sociology is a Martial Art (dir.) Pierre Carles.

Bourdieu, Pierre, & Passeron, Jean Claude. (1990). Reproduction in Education, Society, and Culture. London: Sage.

Bowles, Samuel & Gintis, Herbert. (1976). Schooling in Capitalist America. New York: Basic.

Bracey, Gerald. (2003). “NCLB – Just Say “No!” available on <www.nochildleft.com>

Burbules, Nicholas, & Torres, Carlos. (Eds.). (2000). Globalization and Education: Critical Perspectives. New York: Routledge.

Chomsky, Noam. (2001, October 18). "The New War Against Terror”, Z-Net, Available at http://www.zmag.org/GlobalWatch/chomskymit.htm

Chomsky, Noam. (1999). Profits Over People. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Dorfman, Ariel, & Mattelart, Armand. (1991). How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic. New York: International General.

Friedman, Milton. (1972). Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, Thomas L. (2000). The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization. New York: Random House.

Giroux, Henry A. (2001a). Stealing Innocence: Corporate Culture’s War on Children. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Giroux, Henry A. (2001b). The Mouse that Roared: Disney and the End of Innocence. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Giroux, Henry A. (1997). Channel Surfing: Race Talk and the Destruction of American Youth. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Giroux, Henry A. (1983). Theory and Resistance in Education: a Pedagogy for the Opposition. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey.

Goodman, Robin Truth. (2003). World, Class, Women: Global Literature, Education, Feminism. New York: Routledge.

Goodman, Robin Truth, & Saltman, Kenneth J. (2002). Strange Love, Or How We Learn to Stop Worrying and Love the Market. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Greenhouse, Linda (2003, April 1). “Supreme Court Hears Arguments in Affirmative Action Case," New York Times, April 1, Politics.

Hazen, Don, & Winokur, Julie. (Eds.). (1996). We the Media. New York: The New Press.

Henig, Jeffrey. (1994). Rethinking School Choice. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hill, Dave. (2003, March). “Global Neo-liberalism, the Deformation of Education, and Resistance” The Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies V1n1. Available online: http://www.ieps.org.uk/

Horsley, Scott. (2003). “Tuition Aid Company Draws Mixed Reviews" Morning Edition, National Public Radio, February 21.

Karp, Stan, (2001, Spring). "Bush Plan Fails Schools” Rethinking Schools, V15n3. Available online: http://www.rethinkingschools.org/archive/15_03/Bush153.shtml

Kohn, Alfie, & Shannon, Patrick. (Eds.). (2002). Education, Inc. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Levin, Henry. (Ed.). (2001). Privatizing Education. New York: Westview.

Males, Mike. (1998). Framing Youth: Ten Myths About the Next Generation. Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press.

Males, Mike. (1996). Scapegoat Generation: America’s War Against Adolescents. Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press.

Mathison, Sandra, & Ross, E. Wayne (2003) “The Hegemony of Accountability in Schools and Universities”, Workplace <www.louisville.edu/journal/workplace/issue5p1/mathison.html>

McLaren, Peter, & Farahmandpur, Ramin. (2003). “Critical Revolutionary Pedagogy at Ground Zero.” In Saltman, Kenneth J. and Gabbard, David (Eds.) Education as Enforcement: the Militarization and Corporatization of Schools. New York: Routledge.

Metcalf, Stephen. (2002, January 28). “Reading Between the Lines." The Nation.

Moe, Terry M. (Ed.). (2002). A Primer on America’s Schools. Stanford: Hoover Press.

Molnar, Alex. (1996). Giving Kids the Business. New York: Westview.

Newbart, Dave, Rozek, Dan, & Mendieta, Ana. (2003, March). “Peace Assignment." Red Streak, 6, p1.

Ollman, Bertell. (2002, October). “Lesson Plans: Why So Many Exams?” Z Magazine, V15n11.

Palacios, Miguel. (2002, December 16). “Human Capital Contracts: 'Equity-like’ Instruments for Financing Higher Education.” Policy Analysis 462 (available at www.cato.org)

Saltman, Kenneth J. (2000). Collateral Damage: Corporatizing Public Schools – a Threat to Democracy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Saltman, Kenneth J. (2003). “The Strong Arm of the Law." Body & Society V10n2.

Saltman, Kenneth J., & Gabbard, David. (Eds.).(2003). Education as Enforcement: The Militarization and Corporatization of Schools. New York: Routledge.

Severson, Kim. (2003, January 7.). “Obesity ‘a Threat’ to U.S. Security.” San Fransisco Chronicle, p. A1. Available online: http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2003/01/07/MN166871.DTL

Quart, Alissa. (2003). Branded: The Buying and Selling of Teenagers. New York: Perseus.

Vallas, Paul. (2001, March 2). "Improving academic achievement with freedom and accountability." Testimony to the U. S. Congressional Committee on Education and the Workforce.

Welna, David. (2002, April 8). "Defense budget." National Public Radio.

Wood, Ellen Meiskins. (2000). “Kosovo and the New Imperialism.” In Tariq Ali (Ed.) Masters of the Universe?: NATO’s Balkan Crusade (pp. 190-202). New York: Verso.

Yednak, Crystal. (2003, March 6). “Prep rallies." Redeye, pp. 10-11.

1 This is evident not only in Federally-produced commercials that accuse drug users of supporting terrorism but also of the merging pretexts of drug war and war on terrorism for Plan Colombia. See our discussion of this in the context of education in Goodman & Saltman (2002). The ascendancy of the discourse of national security is further evident by the FBI’s reprioritization of its mission following 9/11. Drug enforcement which was a major priority of the FBI is now not on the top ten list, beaten out by . The majority of the 2 million Americans who remain incarcerated in the U.S. are locked up on drug related charges. In the wake of the U.S. toppling of the Taliban, Afghanistan has regained its place as the number one poppy-growing country in the world.

2 Recently a number of authors in critical education have addressed the extent to which neoliberalism is the dominant ideology of the present moment but also the one most affecting schooling at every level. (Giroux, 2002; Hill, 2003; McLaren, 2003; Goodman & Saltman, 2002; Burbules, 2000; Apple, 2001; Saltman, 2000) Broadly, proponents of neoliberal ideology, celebrate market solutions to all individual and social problems, advocate privatization of goods and services, liberalization of trade, and call for dismantling regulatory and social service dimensions of the state which only interfere with the natural tendency of the market to benefit everybody. In the purview of neoliberal ideology, such public institutions as public schools, public utilities, public healthcare programs, and social security should be subject to privatization. As Chomsky (1999) points out, despite the rhetoric of free trade, advocates of neoliberal ideology seldom want to dismantle those aspects of state bureaucracy responsible for public subsidies of private industries such as agriculture or military, nor do they want to subject artificially supported industries to genuine competition. The central aspects of neoliberalism in U.S. education involve three intertwined phenomena: 1) Structural transformations in terms of funding and resource allocations: the privatization of public schools including voucher schemes, for-profit charter schools, school commercialism initiatives (Hill, 2003),(Levin, 2002), (Moe, 2001), (Saltman, 2000), (Henig, 1996), (Molnar, 1994) (Ascher, 1996), (Giroux), (Apple); 2) the framing of educational policy reform debates and public discourse about education in market terms rather than public terms: the nearly total shift to business language of “choice”, “monopoly”, “competition”, “accountability”, “efficiency”, “delivery”, etc.(Saltman, 2000). The intensified corporate control over meaning-making technologies generally has played a large part in reshaping the public discourse about education. Corporate control over mass media and its increasing role in schooling have both been central to the reimagining of schooling as a market. But schooling is only one of many public goods subject to the call to privatize.; and 3) the ideology of corporate culture in schools (Giroux, 1999; Giroux, 2002; Goodman & Saltman, 2002). This is characterized by the technology fetish, the emphasis on accountability-based methodological reforms like testing and standardization of curriculum while resources are cut, and the like.

3 In neoliberal ideology the individual is conceived privately in economic terms as a consumer or worker rather than publicly and politically as a citizen. The dismantling of AFDC and the creation of Workfare programs initiated under the Clinton administration in fact illustrate these twin demands as they are imposed on citizens: welfare programs represent investment in unproductive individuals with no return on investment while the most important aspect of Workfare is less about financial saving for the state than about making “productive individuals” through the wielding of coercive state power. While the ideological dimension of this reform may trump the financial, it is important not to lose site of the way that within neoliberalism the coercive and disciplinary functions of the state are bolstered while the caregiving functions of the state are dismantled. As Pierre Boudieu suggested, neoliberalism is in this way highly gendered by attacking those institutions such as welfare, education, and healthcare traditionally associated with femininity and strengthening those institutions traditionally associated with masculinity such as military, policing, incarceration, and criminal justice (Bourdieu, 2001). This example of welfare to workfare demonstrates how neoliberalism posits the nation as an enterprise but insists upon the individual as an enterprise as well. Furthermore, this example shows how coercive state power is used to further the financial dictates and ideological demands of neoliberal doctrine.

4 “People feeling insecure, people wary of what the future might hold in store and fearing for their safety, are not truly free to take the risks which collective action demands. They lack the courage to dare and the time to imagine alternative ways of living together; and they are too preoccupied with tasks they cannot share to think of, let alone to devote their energy to, such tasks as can be undertaken only in common” (Bauman, 1999, 5).

5 For important insights on what the new testing really accomplishes see for example, Stan Karp, “Bush Plan Fails Schools” Rethinking Schools, V15n3, Spring 2001. See also, Bertell Ollman, “Lesson Plans: Why So Many Exams?” Z Magazine, V15n11,October 2002. See also, Pierre Bourdieu and Jean Claude Passeron, (1990) Reproduction in Education, Society, and Culture, London: Sage.

6 See the second chapter of Robin Truth Goodman and Kenneth J. Saltman's Strange Love, Or How We Learn to Stop Worrying and Love the Market.

7 “Another illustration of how we regard terrorism is happening right now. The US has just appointed an ambassador to the United Nations to lead the war against terrorism a couple weeks ago. Who is he? Well, his name is John Negroponte. He was the US ambassador in the fiefdom, which is what it is, of Honduras in the early 1980’s. There was a little fuss made about the fact that he must have been aware, as he certainly was, of the large-scale murders and other atrocities that were being carried out by the security forces in Honduras that we were supporting. But that’s a small part of it. As proconsul of Honduras, as he was called there, he was the local supervisor for the terrorist war based in Honduras, for which his government was condemned by the world court and then the Security Council in a vetoed resolution. And he was just appointed as the UN Ambassador to lead the war against terror.” Noam Chomsky from a speech at MIT titled “The New War Against Terror”, October 18, 2001. Available at http://www.zmag.org/GlobalWatch/chomskymit.htm

8 For an example of what I am characterizing as the liberal criticism of corporate involvement in schools see the first section of Education, Inc. See, in particular, the essays by Olson, Hays, and Baker. I criticize these extensively in my essay review of the book in TCRecord.org.

9 In Collateral Damage: Corporatizing Public Schools – a Threat to Democracy I discussed the much publicized situation in Evans, Georgia of a student suspended for wearing a Pepsi shirt on “Coke in Education” day at his public school. The event involved Coke executives teaching classes in the economics, marketing, and science of Coke and culminated in an aerial school picture in which students spelled out the word Coke in red and white with their bodies. My central points were to highlight the extent to which school commercialism initiatives need to be understood in relation to both the broader issues of distribution of educational and other material resources and the broader effort of corporations to propagate corporate understandings of the self and others, a corporate vision for the future, and an understanding of human freedom and choice defined through consumer choice. Part of what was unique in that discussion of commercialism was the observation of students being taught by a corporation to identify not merely as consumers of commodities but as commodities, in that case Coke. This pedagogy that teaches student to identify as commodities has become much more overt as witnessed by the case of two students, Luke McCabe and Chris Barett, public school students in Haddonfield, New Jersey, who sought out corporations to sponsor their college tuition expenses in exchange for advertising the corporation all the time on their clothing. One of the largest credit card companies, First USA, took them up on the offer.

10 Bowles and Gintis remind us that: schools largely function to discipline the future adult population for their participation (or non-participation) in the labor force and political system; that social control is accomplished in part through the internalization of behavioral norms inculcated by schools; that the grading system is the most basic process of rewarding conformity to the social order of the school; that students are rewarded for compliance and submission to authority which is at odds with personal growth and democratic participation; that the hidden and overt curriculum of the school has a central role of depoliticizing class relations of the production process; that economic inequality and personal development are primarily defined by the market, by property, and by power relations that define a capitalist economy; and that racial and gender/sex identification is interwoven with the formation of hierarchy of authority and status in the process.

11 See Michael Apple’s, Educating the Right Way for a critical discussion of this. See also recent work by Gerald Bracey that criticizes No Child Left Behind – www.nochildleft.com. I have referred to this connection between the instrumental logic of the market and the instrumental logic of military discipline in education as “education as enforcement” in Collateral Damage: Corporatizing Public Schools – a Threat to Democracy(2001) Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. My co-edited book by the same name will be out in April of 2003 with Routledge.

12 A number of scholars have recently been working on this relation between neoliberalism, gender, and education including Valerie Walkerdine and Robin Truth Goodman (2003).

13 I have attempted to explain the phenomena of security and insecurity in relation to desire and the body using the sport of bodybuilding to illustrate the points. See Saltman (2003b) “The Strong Arm of the Law.”

Source: http://louisville.edu/journal/workplace/issue5p2/saltman.html

###

Over the past few years, my colleague Scott Harding and I have been chronicling the counter-recruitment movement from the perspective of activists. In this article, I’ll take a different approach and focus on counter-recruitment as viewed by military recruiters. Although it takes a bit of work to find out what they think, military recruiters’ candid views on counter-recruitment reveal that many are concerned at the success of activist campaigns. There’s a strategic advantage to knowing where military recruiters’ vulnerabilities lie, for they give us a peek at the soft underbelly of the all-volunteer force and may suggest areas where counter-recruiters could focus more of their resources. And when military officers spend the time to write reports investigating counter-recruitment — even naming specific groups like Project YANO — activists should consider this a badge of honor. You’re rattling their cage a bit, forcing recruiters to regroup and rethink their strategy. Even though they’ve got all the money and power in this lopsided struggle, you’re getting into their heads.

Over the past few years, my colleague Scott Harding and I have been chronicling the counter-recruitment movement from the perspective of activists. In this article, I’ll take a different approach and focus on counter-recruitment as viewed by military recruiters. Although it takes a bit of work to find out what they think, military recruiters’ candid views on counter-recruitment reveal that many are concerned at the success of activist campaigns. There’s a strategic advantage to knowing where military recruiters’ vulnerabilities lie, for they give us a peek at the soft underbelly of the all-volunteer force and may suggest areas where counter-recruiters could focus more of their resources. And when military officers spend the time to write reports investigating counter-recruitment — even naming specific groups like Project YANO — activists should consider this a badge of honor. You’re rattling their cage a bit, forcing recruiters to regroup and rethink their strategy. Even though they’ve got all the money and power in this lopsided struggle, you’re getting into their heads.

Recently, critics of school commercialism such as Alex Molnar and the Commercialism in Education Research Unit that he directs as well as the U.S. Surgeon General have taken note of just how fat U.S. students are getting. For Molnar, who is one of the nation’s most prominent critics of school commercialism and other authors on his site (

Recently, critics of school commercialism such as Alex Molnar and the Commercialism in Education Research Unit that he directs as well as the U.S. Surgeon General have taken note of just how fat U.S. students are getting. For Molnar, who is one of the nation’s most prominent critics of school commercialism and other authors on his site ( Last week, we made our first SOY visit of the new school year to Austin High School. Tami and I were pleased to be joined by Ben, a Marine Corps veteran and member of Iraq Veterans Against the War who recently moved to Austin. While Ben was a student at the University of North Texas, he did organizing with Rising Tide North America, an environmental group addressing fracking and the tar sands pipeline. It was great to have Ben with us and to be able to stretch out our table of materials so that 3 of us could interact with students. Photos at

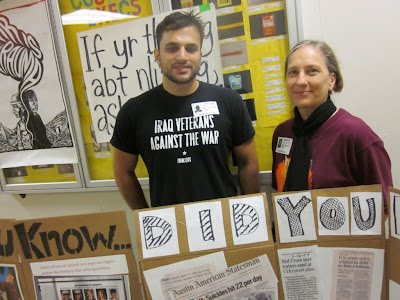

Last week, we made our first SOY visit of the new school year to Austin High School. Tami and I were pleased to be joined by Ben, a Marine Corps veteran and member of Iraq Veterans Against the War who recently moved to Austin. While Ben was a student at the University of North Texas, he did organizing with Rising Tide North America, an environmental group addressing fracking and the tar sands pipeline. It was great to have Ben with us and to be able to stretch out our table of materials so that 3 of us could interact with students. Photos at  I started receiving recruitment emails from a Marine captain with the clockwork regularity characteristic of the military in the beginning of my first semester at Fordham. The Marine captain was vague on most details, but he explicitly listed the benefits of enlisting in colloquial English: “There is no obligation on behalf of the student. You attend during the summer, you get paid. You’ll return to school knowing you have a job opportunity waiting at graduation (15?, 16?) if you wish to accept your commission.” I could easily picture myself without a summer job, and therefore deciding to spend a few weeks in Officer Candidates School in Quantico, Virginia seemed appealing. I did not intend to enlist in the Marines, but if they were willing to pay me to go to this training school, the idea of attending did not seem ridiculous. I never considered unsubscribing from the emails, let alone doing anything about the military’s privileged access to students.

I started receiving recruitment emails from a Marine captain with the clockwork regularity characteristic of the military in the beginning of my first semester at Fordham. The Marine captain was vague on most details, but he explicitly listed the benefits of enlisting in colloquial English: “There is no obligation on behalf of the student. You attend during the summer, you get paid. You’ll return to school knowing you have a job opportunity waiting at graduation (15?, 16?) if you wish to accept your commission.” I could easily picture myself without a summer job, and therefore deciding to spend a few weeks in Officer Candidates School in Quantico, Virginia seemed appealing. I did not intend to enlist in the Marines, but if they were willing to pay me to go to this training school, the idea of attending did not seem ridiculous. I never considered unsubscribing from the emails, let alone doing anything about the military’s privileged access to students.